"Climate change is no longer some far-off problem; it is happening here, it is happening now"

In

1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted that the

greatest single impact of climate change could be on human migration—with

millions of people displaced by shoreline erosion, coastal flooding and

agricultural disruption. Since then various analysts have tried to put numbers

on future flows of climate migrants (sometimes called “climate refugees”)—the

most widely repeated prediction being 200 million by 2050.

Before I write furthur look at this video::

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDKobsJJlRw

The

meteorological impact of climate change can be divided into two distinct

drivers of migration climate processes such as sea-level rise, salinization of

agricultural land, desertification and growing water scarcity, and climate

events such as flooding, storms and glacial lake outburst floods. But

non-climate drivers, such as government policy, population growth and

community-level resilience to natural disaster, are also important. All

contribute to the degree of vulnerability people experience.

The

problem is one of time (the speed of change) and scale (the number of people it

will affect). But the simplistic image of a coastal farmer being forced to pack

up and move to a rich country is not typical. On the contrary, as is already

the case with political refugees, it is likely that the burden of providing for

climate migrants will be borne by the poorest countries—those least responsible

for emissions of greenhouse gases.

The

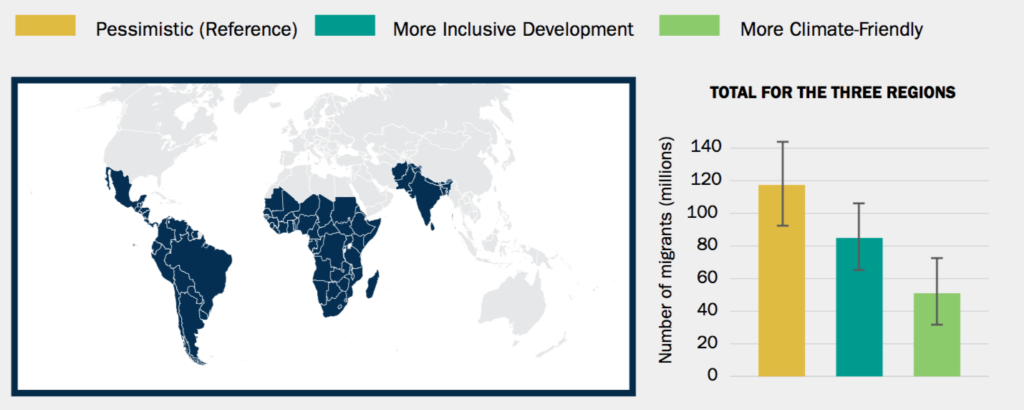

map below (left) shows the regions covered by the analysis, while the chart

(right) shows the total number of internal climate migrants by 2050 estimated

for each of the three scenarios.

|

| “Plausible” internal climate migration totals by 2050 across Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America under three scenarios.Vertical lines represent the 95th percentile confidence interval. Source: World Bank 2018. |

Temporary

migration as an adaptive response to climate stress is already apparent in many

areas. But the picture is nuanced; the ability to migrate is a function of

mobility and resources (both financial and social). In other words, the people

most vulnerable to climate change are not necessarily the ones most likely to

migrate.

|

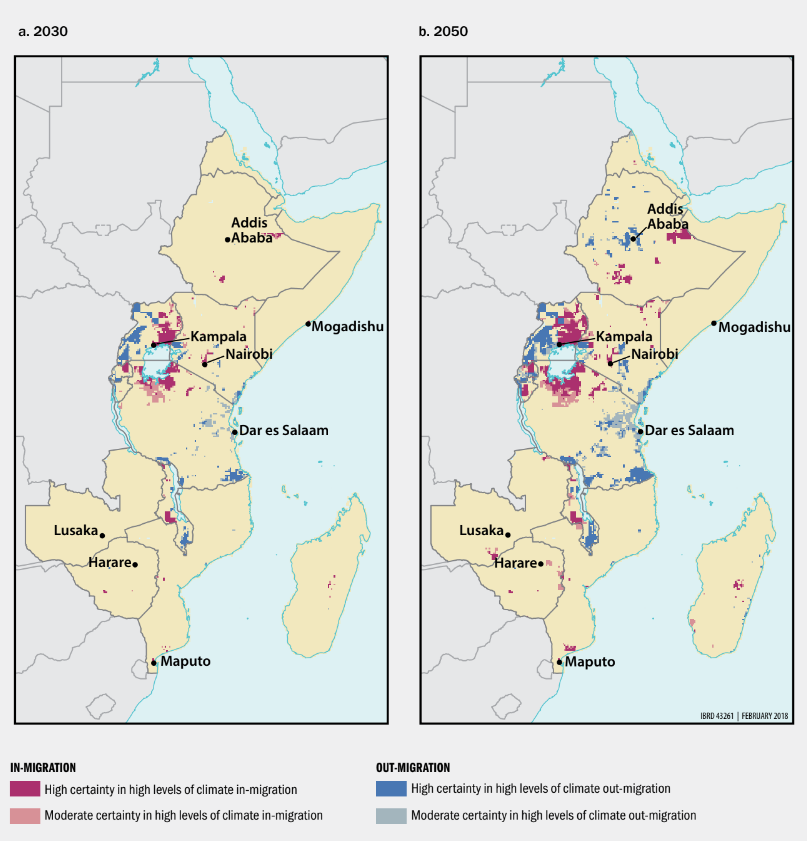

| Areas projected to have high levels of migration towards them (“in-migration”) and away from them (“out-migration”, light and dark blue) due to climate change in East Africa by 2030 (left) and 2050 (right). Source: World Bank 2018. |

Predicting

future flows of climate migrants is complex stymied by a lack of baseline data,

distorted by population growth and reliant on the evolution of climate change

as well as the quantity of future emissions. Nonetheless this paper sets out

three broad scenarios, based on differing emissions forecasts, for what we might

expect. These range from the best case scenario where serious emissions

reduction takes place and a “Marshall Plan” for adaptation is put in place, to

the “business as usual” scenario where the large-scale migration foreseen by

the most gloomy analysis comes true, or is exceeded.

Forced

migration hinders development in at least four ways; by increasing pressure on

urban infrastructure and services, by undermining economic growth, by

increasing the risk of conflict and by leading to worse health, educational and

social indicators among migrants themselves.

However,

there has been a collective, and rather successful, attempt to ignore the scale

of the problem. Forced climate migrants fall through the cracks of

international refugee and immigration policy—and there is considerable

resistance to the idea of expanding the definition of political refugeesto

incorporate climate “refugees”. Meanwhile, large-scale migration is not taken

into account in national adaptation strategies which tend to see migration as a

“failure of adaptation”. So far there is no “home” for climate migrants in the

international community, both literally and figuratively.

Amazing content - Vishnu

ReplyDeleteWe are living in this planet 🌏 as if we had another one to go.. Stop denying the 🌎 is dying.

ReplyDeleteDo something

ReplyDeleteSad but true

ReplyDeleteVery true.

ReplyDeleteThe world seriously needs to do something together

Well Written Vivek ji!!

ReplyDeleteSad and harsh reality 😢

ReplyDeleteVery well written

ReplyDeleteVery Informative

ReplyDeleteThe world needs to wake up!

ReplyDeleteWe should better start working in harmony with nature taking this as a wake up call.

ReplyDeleteKorbo Lorbo Jeetbo

ReplyDeleteThis blog can reduce Kolkata's annual carbon footprint

ReplyDeleteIndeed an alarm call for all of us! Very well put Vivek

ReplyDeleteLearned something new.

ReplyDeleteYou did hit the crux of the problem. Well detailed out, Vivek.

ReplyDeleteWell penned article, Vivek

ReplyDeleteVery informative

ReplyDeleteGreat that we see and discuss the elephant in the room which global leaders give a pass by.

ReplyDeleteInformative read.